Blue about blue / Joyful for joy

An adaptation of my favourite book, or the consequences of my joy, or joy as a tool of adaption.

Adapt:

derivative of the Latin ad, meaning ‘to’ and aptare (from aptus, meaning ‘fit’).

I had a ticket to the theatre adaptation of Bluets in London tonight.

Bluets is a poetic essay by Maggie Nelson, and one of my favourite books. My revelry for which is hard to convey. I’ve noticed this a lot lately, the more I love something (especially books) the less able I am to describe it in a way that doesn’t sound bland and banal.

Bluets is about the colour blue but moreso about the troubles of describing feeling (especially pain), and so it does so through the exploration of the colour blue. This sounds naff but Maggie somehow manages to avoid hyperbole and creates an incredibly nuanced and humanising account of pain, love, loss, sexuality, depression, obsession, art, and of course, blue.

I don’t think I’ve done well describing it. I wonder if this is a lack in (the English) language itself. Here, I’m evoking that quote by literary critic Rita Felski: “Why are we so hyperarticulate about our adversaries and so excruciatingly tongue-tied about our loves?”

All I can express is that my copy of Bluets has various colours of pen in its margins, and that when Bree said she had read it off my bookshelf when she was housesitting for me I felt like she had read my diary. Not because it was a violation of my privacy but because some part of myself is so tied to the object.

So, of course, I bought tickets to the stage show in London. What is less obvious is why I went raving in Lisbon the night before my flight, or why I booked a flight the same day as my ticket to Bluets. I’ll assume you can see where this is going. And honestly, when framed like that it could’ve been a lot worse but I am still an idiot.

I don’t think it’s physically possible for me to regret going to the queer warehouse rave. But I really didn’t need to stay out until 5am and only get two hours of sleep, requiring a nap in London which made me late to the Bluets show. No latecomers they told me at the door. I know the drill. I didn’t have it in be to try and make a case. But I did fantasise about showing the minimum wage, adolescent-looking customer service rep at The Royal Court Theatre my Bluet quote tattoo and screaming, “Don’t you know a deranged literature fan when you see one?!”

The solution was to put me in the naughty corner; a live feed screen of the show tucked into a red walled corner behind a heavy black curtain. I was near homicidal, who the fuck makes a super fan (or anyone for that matter) watch a text explicitly about lost connection and the colour blue alone from within a red box. Now that I’m describing this, it sounds almost funny in its dubious irony which is a promising sign that I will get over this tragedy.

Some time into my insulated/isolated watching experience a woman joined me in the naughty corner. “Did you arrive too late also?” I asked.

“Oh no,” she replied indignantly, “I had a coughing fit and chose to come here instead of being let back in.”

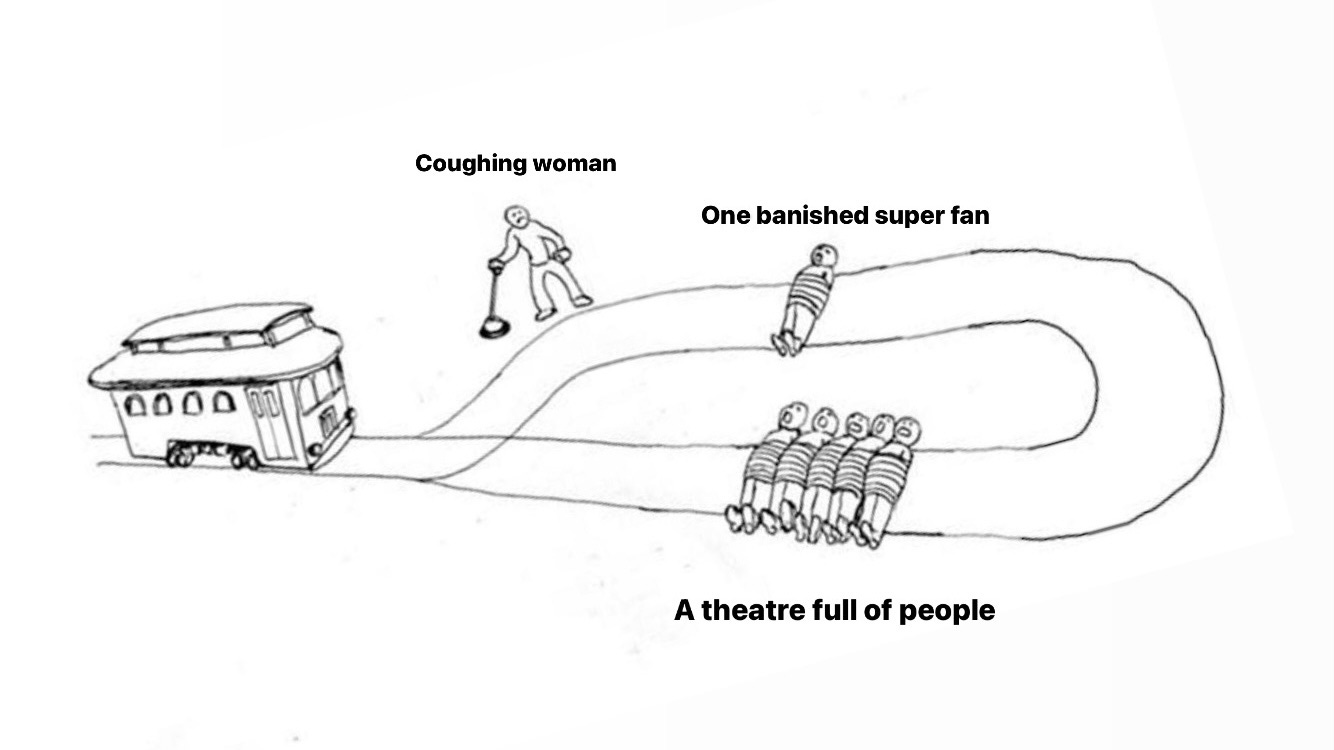

I could’ve killed this woman, in her crimped white blouse and her 2017 lob haircut. I had the intense desire to relinquish the red corner to her and leave her alone to her persistent coughing. Why did disrupting the viewing experience of people in the theatre matter so much to her that she actively chose to remove herself but my watching experience didn’t? A thespian version of the trolly problem, I suppose.

At the time, I struggled to process this series of events, aided by my complete lack of sleep. I kept trying to force some kind of positive spin rather than accept my own disappointment. I thought—and maybe hoped—that my disconnection was unique, because then at least something about the experience was mine and could redeem the evening. This illusion was shattered every few minutes by the woman’s coughing. And solidified by all the conversations I overheard in the foyer and outside the theatre afterwards, which can be summarised to: “the text was excellent but I couldn’t connect to the performance”.

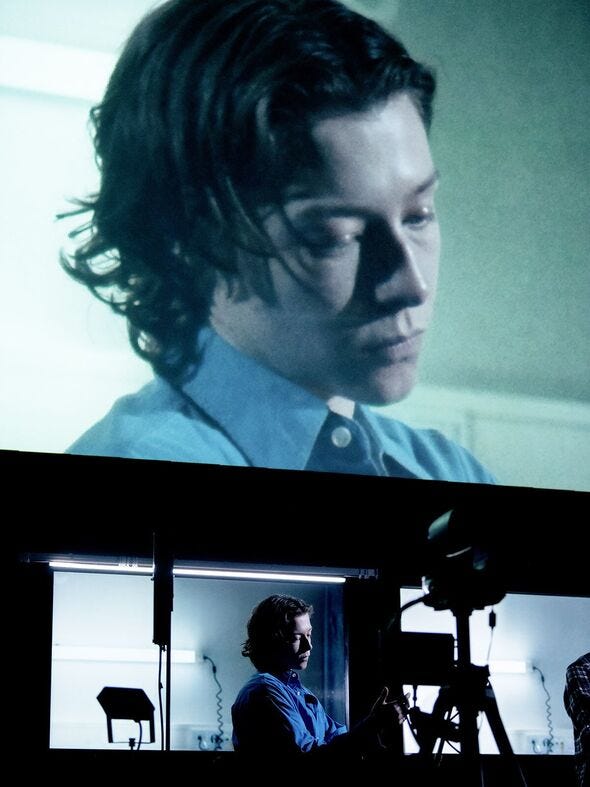

What I didn’t know, and maybe no one else did either, was that this wasn’t a work of theatre but of “live cinema”. What’s live cinema you ask? Well, my program tells me that the script adapter, Margaret Perry, has been perfecting the technique of mixing film and live action for her objective to present images of ‘female experience’. Basically, the actors were on stage and each of them had a screen behind them and a camera before them. Their background would change and the audience could watch the film being produced on a large screen and also see the each of the actors switching between their scenes.

“The novel is a really fragmented object and is all about the interior experience of one woman’s mind. It would’ve been very boring if we had chosen the form of the monologue where it would just be someone talking a lot. Live cinema is great for getting inside someone’s head. It seemed like a perfect match between the material, the interior landscape of a woman’s mind, and the form, which invites you into that interior landscape or maybe doesn’t, depending on how you feel.” —Director of Bluets, Katie Mitchell, in Conversation with Margaret Perry

This artistic choice mixed with my banishment to the naughty corner meant that I was often watching a screen (the tv in front of me) showing a screen (the live cinema on the stage) of someone watching a screen (one of the actors staring into their phone). It all felt beyond meta for a book that is so much about bodies and emotion. The text, even bifurcated through screens, was still the main point of connection. I was so distracted by the artistry of the actors moving between frames that I missed most of the scenes (or should I say fragments) themselves, there was a lot of looks of longing which all three of the actors nailed. However, the constant changing of the minute sets around them and how small their acting had to be to fit into the frame of the camera didn’t suit my scale of the original text. Bluets expanded my world beyond previous self conceptions, namely of what writing can do and make me feel. Through the original text, Nelson obliterates prescriptions of genre and makes theory incredibly sexy.

They changed the order of the text which meant that my favourite line, the fragment of which I have tattooed on my arm, was towards the end, which I was glad about because I got to see Emma Darcy deliver the line, be that refracted through a tv live feed. I had assumed that my disappointment was unique to me and had something to do with the complete and utter lack of blue in my naughty corner. I suppose I had also developed a belief that being banished to the naughty corner was because I indulged too much in my joy the previous night. But like Maggie’s collection of blue objects, must the light and blue be at war? Don’t we need light to have blue? Isn’t the love of blue also the study of light?

“That this blue exists makes my life a remarkable one, just to have seen it. To have seen such beautiful things. To find oneself placed in their midst. Choiceless.”

―Maggie Nelson, Bluets

When I took my eyes off the blurred livestream screen to look at the coughing woman properly, I noticed her glass pendant necklace; a glimmering circle of blue at the centre of her chest. I felt a love for her so intensely in that moment. Through this woman’s annoying presence I got some blue but at what cost? “Suppose that joy were our fundamental condition,” Maggie offers in Bluets. I wonder if this odd connection with the coughing woman—be it punctuated by irritation on my part—stopped me from making my own deep blues in lieu of being kept from the show’s true hues. Which is to suppose, I gave myself over to a kind of gratitude.

Across the street from the theatre, there were busking violinists wearing blue, surely this was on purpose? A ploy towards our sentiments, I wanted to convince myself but I’m always inclined towards mysticism. The true magic of Bluets is how it opens you to worlds of blue of your own. I noticed shapes and shades of blues the whole way home.

How much of what I thought was love was actually limerence? I wonder while a middle aged couple touch each other like teenagers in front of me on the tube. And how much of joy is just being in communion with something?

Is emotional lack marked by a lack of feeling or the language to identify the feeling? At the conference in Lisbon, I spoke to a philosopher (who was more into psychological descriptions of emotion) who said he didn’t associate emotions with bodily feeling. I answered back with a quip about socialisation especially how gendered our emotional allowances are for children. He got a far off look in his eyes like he couldn’t tell what he was feeling, I think I know how he feels.

I think I stayed out so late at the rave, in part, because I was gloating. All these fuckers who had presented on all kinds of ‘productive negativity’ flocked together in search of the ecstatic temporality I try to convince them theoretically matters and holds potentialities. I think it is telling that a group of emotional philosophers all stayed out past 3am at a queer rave after days of watching and participating in panels on emotional injustice, anger, shame, addiction, moral philosophy, etc.

Our blues may not be as dazzling as they seem. Our love might not be love, it might be an obsession, but if we’re lucky this might function to help us self actualise. Dancing through the summer solstice with the group of the coolest nerds I’ve ever met, I was affirmed: Our joy is what we return to, it’s a tool of survival and connection. I’ve never felt more sure of anything. As I moved my body, I was formulating theory. How can I convey this feeling in an academic setting? I wondered, perhaps lamented.

Maybe the adaptation of Bluets didn’t move me because I know my blues aren’t enough. I get back to my accomodation in Earl’s Court and see over the low stone fence that the neighbouring townhouse has an inflatable plastic pool in their courtyard; its vibrant blue full of rotting leaves.

I’ve been thinking that studying joy as a ‘meta feeling’ might be my next step. Put differently, I think joy isn’t just a feeling, it is a mechanism to feel differently about other feelings. For example, I can feel joyful about my disappointment or my anger or joyful about my joy. I like the thought that there are layers of joy we can burrow down into; how far down does it go? Can we feel joyful about feeling joy about our joy?

What implications would this have on our emotional landscapes, our ability to adapt, and what we believe is possible?

Stay tuned for my postgrad work on joyful joy, I guess.

With joy for your joy,

from Roisin

i loved this. that we ever get to experience big feelings is so fucking wonderful. i hate it and love it.