My Irish cousins were born in tracksuits. I, on the other hand, was pulled into this world in just my skin.

When I visit Belfast, my sincerity sticks out, as does my accent and my clothes. There’s extensive photographic evidence: sleeveless brown floral blouse, pinstripe pants, or a bright yellow shirt layered over a skivvy. It’s as if I forget who I think I am or dress as a more exaggerated version of my dorkiest self. I wonder if I subconsciously dress as a caricature because if I’m not authentic then perhaps my difference won’t be authentic either. By drawing attention to my out-of-placeness, I foreclose the possibility of trying to fit in and therefore the failure of fitting. I wonder if this also makes belonging impossible.

My rare attempts to fit in (wearing my cousin’s football shirt and chatting with a group of uni students at Madden’s bar) quickly turned sour. Such as when my Granny made a joke that I shouldn’t be wearing the bright green footy kit in the loyalist neighborhood she lives in now. Or giddy on Guinness, I made the faux pas of asking where one of the students grew up. “We don’t ask that in Belfast,” he replied gravely. There are all these silent social rules I don’t know or easily forget because I didn’t grow up in the tangles of secularism. I’m also let off easy because I’m not wearing a tracksuit.

*

On the weekend, Mum and I went to see the biopic for the West Belfast rap group Kneecap. We were one of three pairs in cinema 8, and the only ones who laughed the entire film. I wondered about the silence perched behind us. Did they not get the jokes? Were they Irish? Am I?

The film is a dramatisation about how Kneecap formed but is also about survivance, secularism, class, and language— the Indigenous Irish language specifically and how rap is one of the latest strategies to keep it alive. I don’t want to downplay the significance of this. Not only was the North of Ireland the first British colony, some 850 years ago, but it was also home to the longest-running violent conflict in contemporary European history, commonly and euphemistically known as the Troubles. Ending, in part, with the Good Friday Agreement in 1998.

I also think the film is about masculinity and how masculinity and class intersect in “post-conflict” Belfast, leading to a deficiency in models of masculinity. This isn’t unique to Belfast but is further complicated by the Troubles and its lineage. The peace process has not created any significant shifts in a deeply divided political system or removed residential, social and educational segregation. For example, only 7% of children go to integrated schools (for both Protestant and Catholics).

In some ways, conflict became the culture. The role of young men during the conflict was often to be the ‘defenders’ or ‘protectors’ of their communities. The so called ‘crisis of masculinity’ (when working-class masculinities are displaced without the blue-collar jobs, that two generations ago could feed and house a whole family) is exacerbated in places like Northern Ireland, where 19% of people live in relative income poverty, and 16% (approximately 303,000) in absolute poverty.

“We always say we have more in common with working class people—on whatever side of the divide—than any rich person in Dublin, even though we have the same passport. People want to be outraged without looking into the facts. A worker’s revolution is the way forward rather than one based on a God that might not even exist.” — Mo Chara from Kneecap in Interview

When I was in Belfast, I was aware of my desire to dress like the men in my family. There was a sudden and strange allure to a slim leg tracksuit cuffed above a trainer. There was a clean, ironed look to their poly/cotton. I imagined owning a “nice pair” of Nike joggers and only getting them out on special occasions like a job interview at the Spar or for Mass (attended only when the Australian cousin asks to go or when someone has died).

I know that in some ways, it is harder to be trans* in Ireland than elsewhere right now. Both sides of politics in Ireland just voted against gender affirming care. When I was traveling around Ireland, I got the sense that being a woman is harder there too. Women seem to take up less space in the zeitgeist and when they do appear it’s often as mothers, sometimes housebound, like the Ma in the Kneecap biopic. Maybe, being a woman in Ireland is just different in a way that felt regressive to me. I also might’ve just been projecting. Maybe, I just found it harder for my queerness, my non-binary/trans*ness, to coexist with the unknowns and cultural absences of my half Irishness.

It could be argued that Kneecap exemplifies a hypermasculine archetype, which is both nostalgic for the role young men played during the Troubles; thereby ‘stuck’ somewhere between a ceasefire mentality and ambiguous messages of peacebuilding. Kneecap are aggressive in ways which are both divisive and exciting. They frequently sample news segments calling attention to their divisiveness. They wear their disgrace like a badge of honour. “You cunts made us famous”, they rap on It’s Been Ages in reference to the negative press they receive. It would be a reductive generalization to say that the purpose of rap is to piss people off. But what would be the point in making hip hop (or any art for that matter) that is palatable to everyone?

Kneecap are the first to rap in Irish. Speaking Irish is a political act. Especially in the North, where only 12% of people have ‘some ability’ to speak it. but as Jon Blistein in Rolling Stone points out, “many of their critics seem to see Kneecap’s very use of the Irish language as an inherently politically divisive act, rather than just something Irish speakers would do. “ They’ve gotten a lot of attention for their music, in part, because they are rapping in language about sex, drugs, and violence. Leading to people from all sides to vilify them and their music. From the outside, it seems like a classic case of reclamation; ‘you think I’m scum? I’ll show you scum’ kind of attitude. In this way, it’s an outlet for repressed rage and also a self-fulfilling prophecy.

None of this is unique to Kneecap, aggression and reclaiming stereotypes is employed by most— if not all— rap music. It is and always has been a way of speaking back to the stereotypes of the oppressed, clapping back at the system, and empowering minoritised communities through a kind of consciousness raising. But how do we know this is doing more than just perpetuating stereotypes? When the lads from West Belfast writing about their downtrodden realities become archetypal, is being ‘drug dealing pagan’ or a sellout solidified as the only models of masculinity? Weren’t they already seen as the only available choices? Maybe the question we want to be asking is: how do we make new ways to be a man? And then the better question is: why look to rappers to write that handbook?

Kneecap’s tracks are often rage/rave fantasies but are executed with excess, winking with humour and self-awareness. However, in both their music and their biopic, Kneecap intentionally obscure how truthful or sincere they are being. “It’s an exaggeration,” they admit in an interview with Next Best Picture, “nobody wants fucking boring, mundane daily life.” They built personas in their music and felt the need to match this energy onscreen. You can see this exaggeration clearly in their costumes in the film, swapping out their usual smick grey and black for garish, colourful tracksuits.

*

After the film, I turned to Mum and said, “I feel the need to go shopping for a tracksuit.” In the Rebel Sport change rooms, I tried on a garish green and burgundy Adidas tracksuit. The slim joggers clung to my thighs in a way that made me want to peel my skin off. My hips gave me away. But in a black pair of Nike trackies with a black and green shell jacket, I felt inexplicably invincible. Not so invincible that I wanted to rob a vet (like the Kneecap song ‘Rhino Ket’). More like, I wanted to cook my Granny lunch before heading up to the Star for a pint. I wanted to catch the Glider from West to East and back again. A kind of lax masculinity took over me, a desire to care but conceal and reveal this desire to care in equal measure.

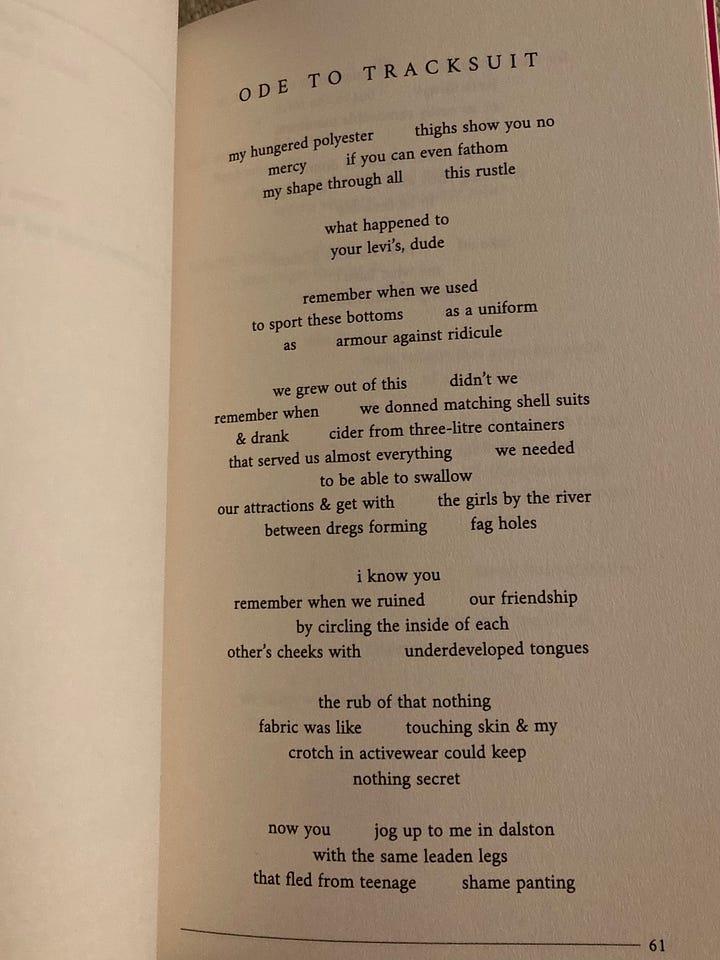

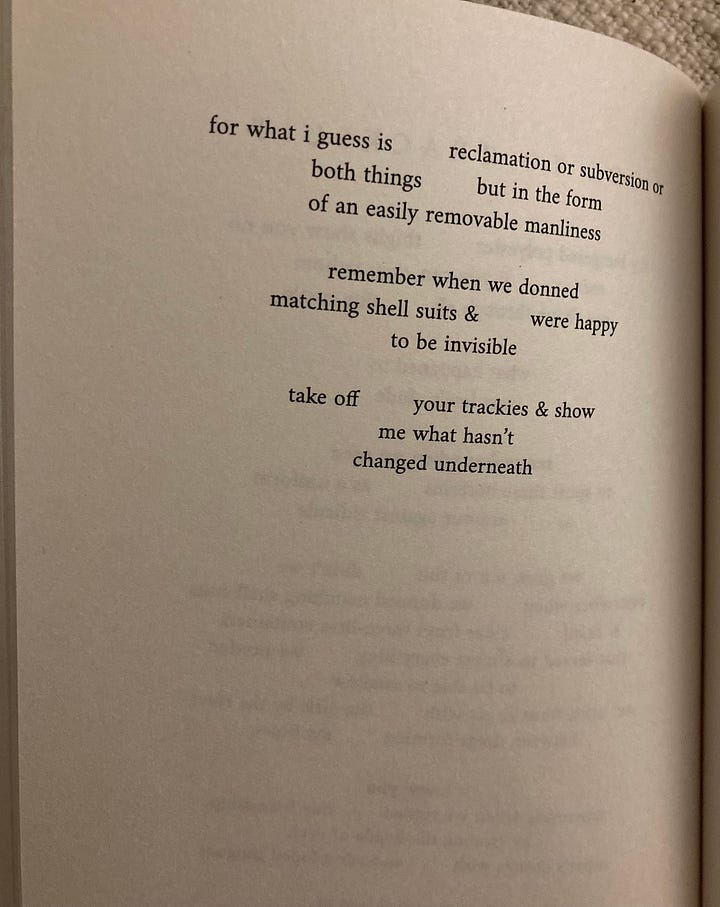

I was reminded of the poem Ode to Tracksuit by Peter Scalpello (a queer poet from Glasgow):

This poem is fucking magic because it manages the seemingly impossible and glaringly obvious: to make the tracksuit sexy and queer. There is something tough about the tracksuit but it’s also revealing, clinging to certain parts of the body. Despite its utilitarian edge, the tracksuit is not a suit of armour. Even a small drizzle soaks through, revealing that it is nothing more than a second skin.

I bought the overpriced Nike ensemble and lounged around the rest of the day “in the form / of an easy removal manliness.” I don’t care whether this polyester masculinity is “reclamation or subversion or both things.” I’ve got bigger things to worry about. Like the fact that I’m writing this in the language of only half of me. There's a dormant desire within my impulse purchased tracksuit. This desire could only be named in the language unknown by me. What would be unlocked in me, in my world, if I could speak my motherland’s tongue?

There is a perpetual identity crisis to being made of halves. My half British whiteness is obscured by generations of what they call Australian. My half Irishness is closer, smuggled in by the skin of my mum’s teeth and marking me in the form of a Gaelic name. These halves are further halved by law, in the name of peace. I’m half British, half Irish, and my half Irishness is half British. I’d say I was Australian if I knew what that meant. To say I am Australian feels like the absence of an identity. I’m nothing and everything, my halves are halved in half. In this way, my body mirrors Northern Ireland.

There is a terrific terror in having a name in a language you cannot speak. I am only known as Rosh in the Southern hemisphere. Partly because we love nicknames here. Mostly because people can’t pronounce my name and give up and I let them. There’s a further divide in pronunciation between the North of Ireland and the Republic. Pronounced “Ro-sheen” where the tv channels are British and “Rosh-een” down south. Everyone in Ireland asked me which way I pronounce it. I didn’t have an answer. I’m used to shrugging my way through this fumbled identity. I’m used to bristling against the world.

I drive around town in my new Nike tracksuit listening to Kneecap rap in Gaelic. I don’t think I’ll ever know how I want to say my name unless I cut out my tongue and replace it with one that was born in a tracksuit. Every time I move my arms my polyester shell swishes, this is my very own Ode to Tracksuit. Through this rustle my shape is unfathomable but my blood thumps along. My blood knows what these words never will.

Tá muid beo!

With joy,

from Róisín

Oww you’re brilliant. Those last three paragraphs really struck hard, particularly that last line! Ouch!

Thank you for naming it — that ‘terrific terror of having a name in a language you cannot speak’; that feeling of being ‘nothing and everything’.

And maybe it could be enough, just to be throbbing with a blood that knows more than our words ever will.

PS. New band name: Giddy on Guinness

I love this. I feel this way about my Scottishness, and love the way Gaelic feels in my mouth. I wonder what it would be like for the mountains to just swallow me whole.